IBM believes that sensors and cognitive computing can help monitor water quality.

Citizens of New York state just might be thanking a handful of Dubliners for cleaner water in Lake George, if a new pilot IoT program with IBM Research goes well. The technology company is teaming up with the Dublin City University (DCU) Water Institute to use water sensor technologies in new ways. Although Lake George is the first project, DCU hopes to deploy sensors around Ireland in the near future as well.

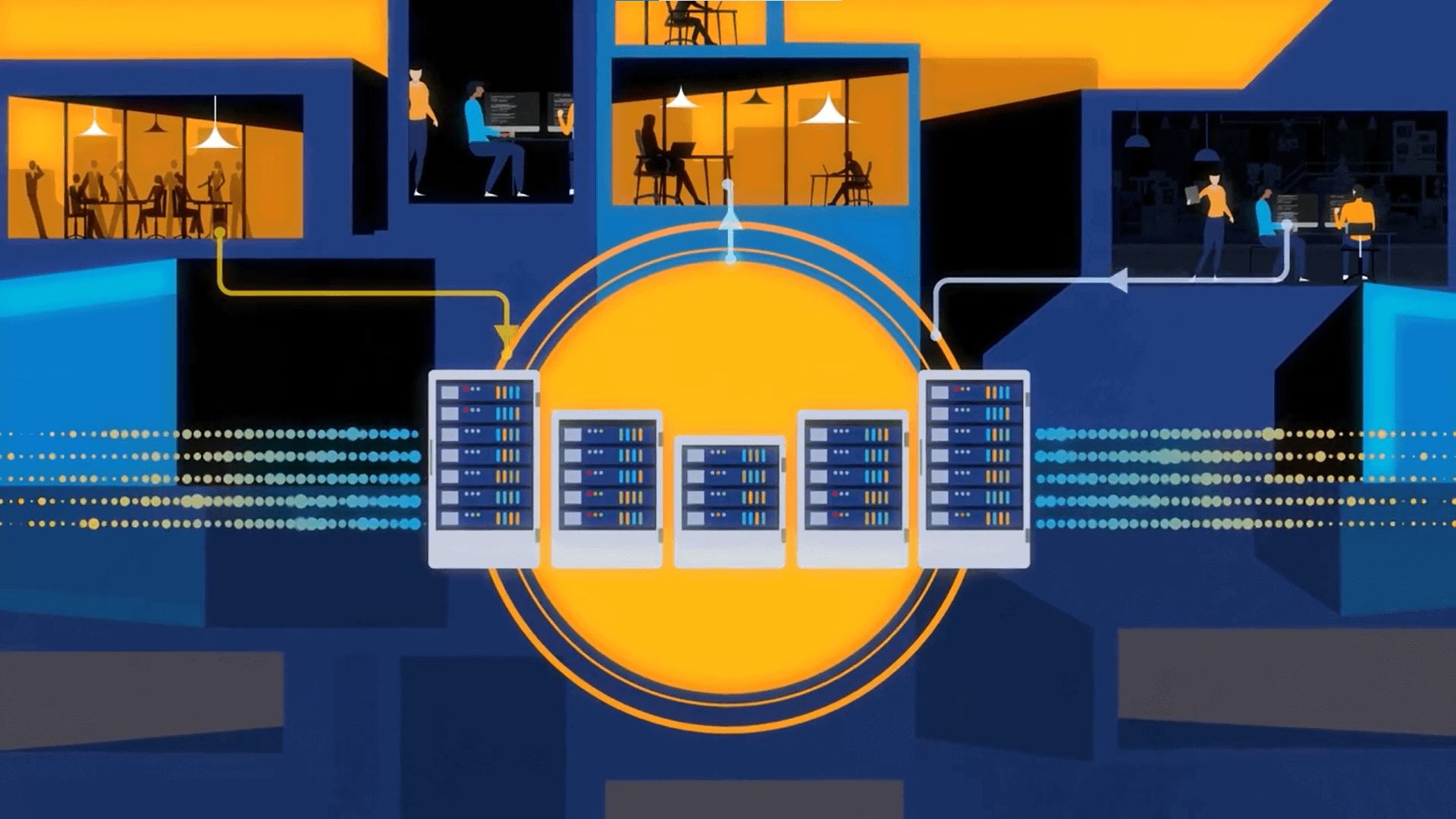

DCU will supply the sensor technology for these pilot programs, while IBM is offering its machine learning and cognitive IoT technologies.

Water sensor technologies: cheaper and smarter

The Ireland-built sensors are capable of monitoring a number of key components of water quality, such as physical, chemical, and biological parameters. And while they’re not necessarily an innovation, what sets DCU’s sensors apart is the ability to deploy them at lower costs than existing commercial offerings.

“The technologies developed during this important collaboration will aim to disrupt the current norms of costly sensors limiting their distribution at IoT scale” and will “provide really valuable information which supports better decision-making about valuable water resources,” said Professor Fiona Regan, director of the DCU Water Institute.

The idea is that by driving down the costs of an IoT network of water quality sensors, more government agencies can deploy them to collect data. According to IBM and DCU, these sensors could be used to detect water quality changes with multiple cause. One example is helping environmental organizations better manage agricultural runoff, which can pollute lakes and rivers.

IBM brings cognitive to the outdoors

For the Lake George project, IBM Research engineers received a research-grade optical colorimetric sensor (OCS) from DCU, and deployed the OCS into a major tributary that flows into the freshwater lake. They hope to track data from this sensor to understand the lake’s current health, and then visualize changes over time.

On the cognitive front, IBM is bringing deep learning capabilities to the sensor platform. By embedding advanced analytic capabilities directly into the sensor, or the sensor’s IoT platform, cognitive algorithms can be used to detect subtle trends without direct human intervention or manual analysis.

Back in 2013, scientists from the EPA and U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) conducted a wide-ranging test on the effects of agricultural runoff on 100 streams across the Midwest. One scientist, biologist Diana Papoulias from the USGS, said, “These aren’t the kinds of studies that are done routinely, because they are pretty difficult to do.”

IBM and DCU’s cheaper and smarter sensor package just make that work a little easier. Not only can the sensors monitor long-term changes to a body of water, but can also intelligently determine when conditions are right for a potential public health hazard. For example, cyanobacteria like to grow when there are lots of nutrients, warm weather, and little wind. These create algae blooms, which can be harmful to humans and animals. If the sensor itself can detect and recognize conditions cyanobacteria would love, it could warn environmental management teams hours or days earlier than manual observations or hoping someone will call a public health hotline.

“Over the next few years, we believe that Internet of Things technologies will play an important role in helping protect the environment and natural resources,” said Harry Kolar, a distinguished engineer at IBM Research. “We are excited to leverage IBM’s expertise in cognitive and IoT environmental monitoring and management with the DCU Water Institute to help advance the future of water management.”

The future of IoT and the environment

As we’ve pointed out before when reporting on other IoT-based conservation efforts, such as saving the dugong sea creatures in the Philippines, conservationists have been thinking like IoT technologists for for decades now. Every bird or bear tagged with a radio device is a good example. The difference now is that these technologies are getting smaller, cheaper, and smarter than ever before, which opens new possibilities.

In the end, it’s not surprising to see IBM bring their cognitive expertise to environmental issues. Back in the ‘60s and ‘70s, IBM were pioneers in developing corporate environmental policies that prioritized the conservation of natural resources, minimization of waste or pollution, and giving preference for renewable energy.

We’re curious to see how they can leverage Watson to make even more headway in this field. No one might think of their local lake as being “smart,” but if IBM and DCU have their way, it seems that’s exactly the future we’ll see. And to us, that’s the wonderful thing about IoT—the applications and the benefits are nearly endless.