As the devices that make up IoT become part of our everyday infrastructure, what are we doing to disaster-proof this massive new distributed network?

When floods, hurricanes, earthquakes, and tornadoes strike, everything — including human lives — suddenly becomes a real-time concern. However, confusion tends to reign when power and systems are down. Can technology help provide government authorities a clear view on what is going on within a region afflicted by a natural disaster? A group of researchers says emerging technologies — especially Internet of Things technology based on networks of independent nodes or sensors — can make the difference.

In a paper published by MDPI, researchers from several universities in the Americas, led by Gustavo Furquim of the Federal Institute of Education, Science, and Technology of São Paulo, describe the results to date from a network called SENDI, or “System for dEtecting and forecasting Natural Disasters” based on IoT. SENDI is a fault-tolerant system based on IoT, machine learning and wireless sensor networks for the detection and forecasting of natural disasters and the issuing of alerts.

The system was installed in the Brazilian town of São Carlos to carry out data collection from rainfall and rivers in the region. The purpose is to monitor, analyze the data, detect flash floods, and present online information about rivers in urban areas.

While wireless sensor networks and the Internet of Things show a great deal of success in measuring weather events, they are vulnerable to the same calamities as well. Furquim and his team also note that current wireless systems do not have forecasting capability.

See also: Friend or foe? In network infrastructure, big data holds the key

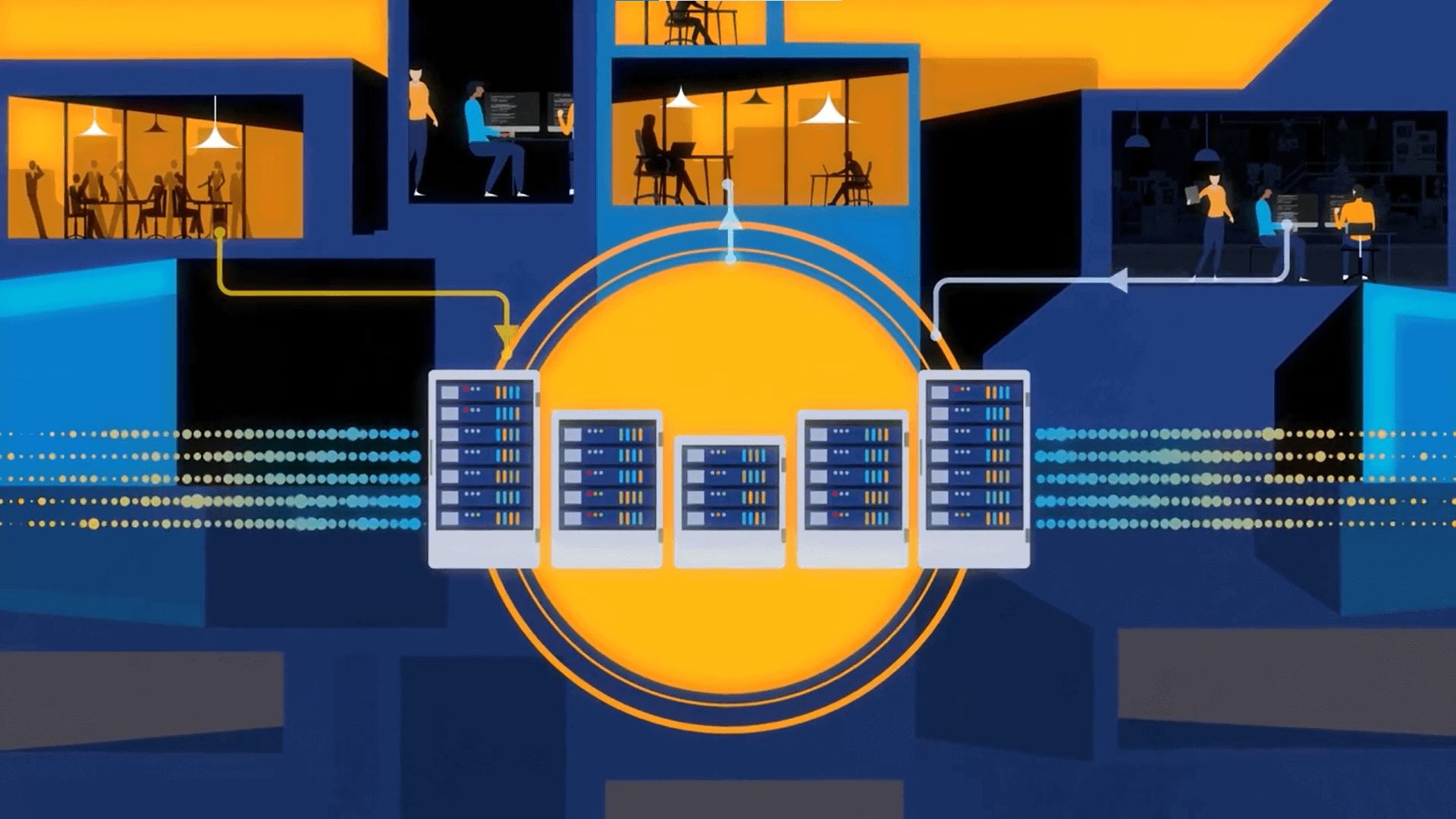

The SENDI system they tested extends the existing wireless sensor networks through a more highly integrated approach between devices and remote services. The nodes of a wireless sensor network “can be seen as smart objects” that support “diversity in data collection from different types of sensors; the possible use of these data via the Internet and collective intelligence among all/some nodes, based on information about multiple nodes and not only about the situation and data of a single one,” the researchers said.

The sensor networks are “based on IP by using emerging standards, such as 6LoWPAN/IPv6, which allow the most diverse objects in IoT to be connected with each other,” they relate. In addition, the intelligent sensor network now employs cloud computing and social networks to help in the forecasting and issue online warnings. The sensor nodes can also “communicate with nearby devices which share the same technology and propagate the information and forecasts.”

In the São Carlos project, “all the nodes use sensors which read the water pressure on the river bed and convert this value into the depth of the river, measured in centimeters, except in the case of the nodes where the sensor is a rain gauge that measures the volume of rain in the area,” Furquim and his co-authors state. “Another node that stands out from the others is the node installed in the mall of the town, which is also equipped with a camera that takes pictures of the monitored region.” The data used for this study were collected over a one-year period from the node in the mall, and the readings of the river level were taken at one-minute intervals.

The researchers report that SENDI “was able to make predictions with a high degree of accuracy, even in an unfavorable scenario.” The main issue encountered was the fact there were not enough nodes to provide the complete picture local authorities needed to assess where the most flood damage was occurring. As the IoT grows and more devices and sensors are connected, prospects for more adept real-time management of disasters will improve dramatically.